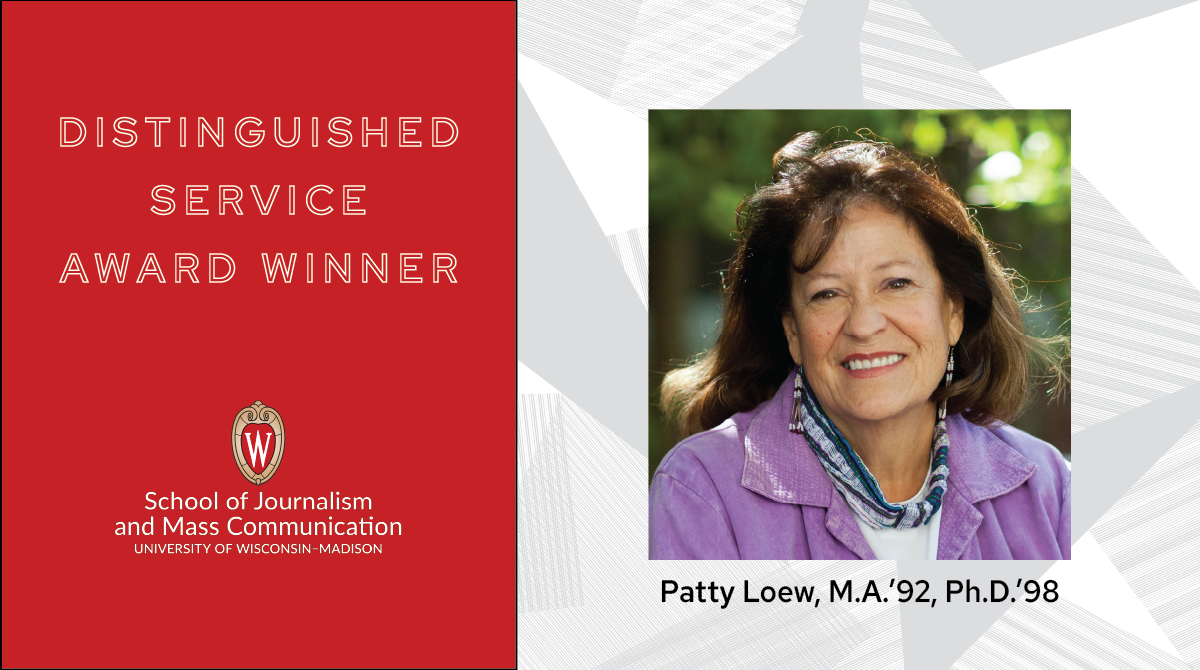

Dr. Patty Loew is Professor Emerita at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications and one of this year’s Distinguished Service Award winners. She retired in August 2023 after directing the Center for Native American and Indigenous Research at Northwestern University and teaching at the Medill School for seven years. A citizen of Mashkiiziibiig, the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, Dr. Loew is a former broadcast journalist in public and commercial television. She has authored acclaimed books like Native People of Wisconsin, Seventh Generation Earth Ethics and Indian Nations of Wisconsin, which is used by 20,000 Wisconsin school children as a social studies text.

In addition to books, Loew has produced many documentaries, including the award-winning Way of the Warrior, which aired nationally on PBS on 2007 and 2011. She works extensively with Native youth, teaching digital storytelling skills as a way to grow the next generation of Native storytellers and land stewards.

Prior to her role at Northwestern, Loew was a professor at UW-Madison. She is Professor Emerita, UW-Extension and an Honorary Fellow in the Department of Civil Society and Community Studies in the UW-Madison School of Human Ecology. In 2011, Dr. Loew received the Distinguished Alumni Award from UW-LaCrosse and in 2010, Outstanding Woman of Color awards from both UW-Madison and the Universities of Wisconsin.

Loew recently returned to Madison to take care of her 100-year-old mother and to be closer to her children and grandchild.

What is the most important lesson you learned in the J-School?

I think the most important lesson I learned was how to be a good mentor. I was fortunate to have professors who were not only brilliant but also generous with their time. They were patient with someone like me who returned to school later in life. I have tried to model that generosity with my own graduate students and instill in them the confidence and desire to make meaningful contributions to academia, nonprofit sectors, and tribal communities.

Do you have a favorite J-School memory?

My experience as a grad student was not typical. While going to graduate school, I worked two jobs: anchoring the 5, 6, and 10 p.m. newscasts for the ABC affiliate in Madison and co-hosting a weekly news and public affairs program for PBS Wisconsin. I also gave birth to two children during this period. My most vivid memory was finishing my master’s thesis– dotting the last “i,” crossing the last “t,” delivering my manuscript to my advisor Steve Vaughn, and two hours later going into labor with my second child. No one could ever accuse me of not being efficient.

What does this award mean to you?

I think this award validates the choices I’ve made in my journalism career. The most important contribution I’ve wanted to make is to grow the next generation of Native American storytellers and land stewards.

It gives me such satisfaction to know that I’ve shepherded nearly a dozen Native scholars and scores of Indigenous allies into journalism careers. I am exquisitely proud of the fine work they do, especially on topics of social justice and environmental racism.

If I’ve distinguished myself, it’s really in the area of outreach–coordinating media camps for tribal teenagers and writing the social studies textbook that 25,000 Wisconsin school kids use each year to study Native history, treaty rights, and sovereignty in Wisconsin.

That’s the best part of me.

So, it’s meaningful to me that the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication finds my work meritorious and deserving of an award.

What advice would you give to your college self?

Get more sleep!

Favorite Madison hangout?

I know that this is going to sound incredibly dull, but my favorite place to hang out during grad school was the 5th floor (Native American topics) of the Wisconsin Historical Society Library.

Once, while looking for a Native American manuscript, I had a surreal experience in the stacks. The overhead light was burned out in the E-98 section and the book I needed was hidden in the darkness. I had a key light for my old Subaru that emitted a very narrow, pale green light, which I used to search for my document.

As I swept the shelves with my pitiful, little light, I noticed a thick, black tome on an upper shelf just out of reach. After seeing it in my peripheral vision for maybe the third time, I finally stood on my tiptoes and poked at it with the eraser end of a number 2 pencil.

It tumbled into my hands, serendipitously opened to the 1909 testimony of my great-uncle and other family members at a congressional hearing.

Wisconsin Senator “Fighting Bob” LaFollette, who chaired the US Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, had brought his colleagues to Mashkiiziibiig (the Bad River Ojibwe Reservation), where tribal members were being harassed by the timber barons. My ancestor, Antoine Denomie, who edited the reservation’s newspaper, The Odanah Star, had regularly written about their skullduggery. That 1,100-page government report became key research in my dissertation.

Favorite J-School subject?

Because I returned to school later in life and because my full-time job limited me to registering for just one class each semester, I approached my graduate experience with a sense of gratitude. My job as a broadcast journalist was to condense complicated stories into one-minute packages and 15-second headlines. A 25-page research paper assignment represented freedom. I reintroduced myself to adjectives; I rejoiced in providing context. I had no hourly deadlines. Papers were due at the end of the semester, not by 6 o’clock each night.

My favorite subject was whatever my current class was. I was so grateful to be in it! However, the class that probably benefited me the most was qualitative research methods. It helped me write my history books and biographies and it made me think more critically about how to decolonize research. It also influenced how I taught my own journalism students at UW-Madison and Northwestern to include Indigenous frameworks and methodology.